Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaI didn’t set out to do it, but it happened anyway.

The main character in one of my works-in-progress is “ignorant,” “priggish” and “holier-than-thou,” according to a member of my writing group. In other words, the character is downright unlikeable.

And I’m fine with that.

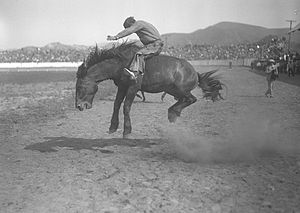

Unlikeable heroes – sometimes called antiheroes – are fascinating. Like Travis Bickle in Taxi (shown above), they tend to be characters we identify with and love to watch in action, whether we admit it or not.

But there is a trick to writing an unlikeable character – a balance, a trade-off, a way to avoid alienating the audience from the character (although other characters may be so alienated).

Before we get to that trick, let’s look at three reasons why unlikeable characters are so appealing:

Unlikeable characters mirror our own struggles for acceptance and to get ahead. In the British historical drama Downton Abbey (airing Sunday evenings on PBS), Thomas is a self-serving, ambitious, and ingratiating footman who steals and lies. Full of arrogance, he lords it over the other servants of the house when he is appointed military liaison during World War I. After the war, he tries to get ahead by dabbling in the black market.

His schemes invariably fail, sometimes with laughable results, but he keeps trying, and, in the 2011 Christmas Special, he finally wins a long sought-after promotion.

Thomas might better be classified as an antagonist than an antihero, except he is so wonderfully complex part of us hopes he will succeed. When several members of both the family and staff take ill with the Spanish flu, Thomas pitches in – free of charge (“Consider it rent,” he says) – to help out. We know it’s just another scheme to ingratiate himself further, but part of us wants to believe Thomas is indeed changing or that he will see that by helping others, he can help himself. We know this probably won’t happen, but there’s hope.

Unlikeable characters express struggles within us. Wolverine, the iconic X-Men antihero, began as an antisocial, mildly sociopathic misfit who antagonized his teammates, was contantly on the verge of going berserk, and possibly violated one of the oldest codes for super-heroes by killing villains. In one early scene (Uncanny X-Men # 96, December 1975), Wolverine does indeed go berserk and hacks and slashes away at a monstrous enemy. Afterwards, he expresses regret that many years of discipline and prayer had failed to bring his animalistic side under control – but also astonishment that he enjoyed inflicting such carnage!

Wolverine represents our sometimes conflicting desires to control less savory aspects of our characters and to finally give in to and revel in those traits. It’s no coincidence that Wolvie – a character with claws and a badass attitude – remains one of Marvel’s most popular heroes nearly 40 years after his debut. But it’s his inner conflicts that make him relatable.

Unlikeable characters represent our own desire to persevere in spite of the unfairness of life. Wildfire, a member of the Legion of Super-Heroes, is a hero without a body. Converted by accident into a being of pure energy, he interacts with his fellow Legionnaires, villains, and everyone else through a containment suit that permanently separates him from others. This condition magnifies his already hot-headed personality: he antagonizes his teammates, much like Wolverine does.

However, Wildfire proved so popular with fans that he was elected leader of the Legion, giving him even more opportunities to antagonize his teammates with his brusqueness, temper, and autocratic ways.

Yet for all of his power and popularity, Wildfire can’t do the things ordinary people can. This was driven home when he eventually developed a relationship with fellow Legionnaire Dawnstar. Despite his frustration, sexual and otherwise, Wildfire became the Legionnaire many fans rooted for. He never cared what other Legionnaires thought of him, and he never gave up.

Now for that trick to writing unlikeable characters:

Each of these characters bonds with at least one other character, and the interaction between them helps bring out the unlikeable character’s humanity. Thus, Thomas has Miss O’Brien (who, herself, is rather unlikeable), the older, vengeful spinster who takes an almost motherly interest in him. She becomes his co-conspirator in the black market scheme and is there to sympathize with him when it goes horribly wrong.

Wolverine and Wildfire both had doomed relationships with Phoenix and Dawnstar, respectively. (And, in the first X-Men film, Wolverine is given a protégée of sorts in Rogue – a relationship which did not exist in the original comics.)

Showing your unlikeable character as being capable of a relationship – a friendship, a love affair, a confidence – keeps the character from becoming a total misanthrope. More, it gives us “permission” to like the unlikeable.

What do you think? Are any of your characters unlikeable?