|

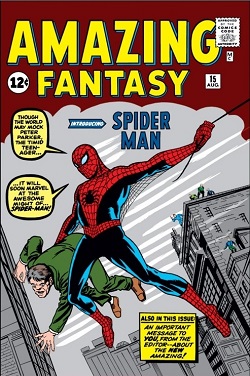

All characters and images™ and ©

DC Comics Inc. |

It’s a cliché these days: Super-hero X died, but he got better.

At least since

"The Death of Superman," comic book deaths have been a valuable marketing tool—a way to lure mainstream media into paying attention to comics by suggesting that some iconic hero of our collective childhood is going to bite the dust permanently.

But for comics fans, death has become a joke. We know that sooner or later the popularity and cash cow value of characters such as Superman and Captain America, who was also killed off in a major media blitz a few years ago, will dictate their eventual resurrection.

Even for minor characters, death is usually a sales ploy—a reminder that characters are commodities to be bought and sold however the publisher sees fit.

And yet, if handled correctly, the death of a super-hero can be meaningful and moving, and can resonate with fans years, even decades, later.

One of the most memorable deaths for me was that of Invisible Kid, a long-time member of Superboy’s friends from the future, the

Legion of Super-Heroes, in

Superboy # 203 (July-August 1974).

"Massacre by Remote Control" was written by

Cary Bates and drawn by

Mike Grell, marking the latter’s ascension as regular Legion artist. (Grell had debuted the previous issue, inking a story pencilled by his predecessor, Dave Cockrum).

As a writer, Bates is seldom remembered fondly by Legion fans, and with good reason. He played fast and loose with established Legion continuity and expressed his dislike for writing super-team books by featuring only a handful of Legionnaires in each story. (In Superboy # 200, for example, he sends only four Legionnaires after the villain, even though the entire team plus wedding guests—a total of about 50 super-heroes—are present.)

Nevertheless, Bates was a master plotter who weaved twists and turns in such a way that they seemed inevitable (as the developments in every a story should be). More, he could write a complete, satisfying story in a single issue—a skill all but forgotten in the modern era of story decompression.

Bates also deserves to be remembered for reinvigorating the Legion in the early ‘70s. Partnering with Cockrum, he updated the team with more dynamic stories and new characters such as Wildfire (a hero) and Tyr (a villain). But Bates also cleaned house by dumping characters whose powers were considered too lame for the ‘70s, including Bouncing Boy and Duo Damsel (who married) and Invisible Kid.

But if Invisible Kid had to die, at least he died in style.

Massacre by Validus

The story begins as Invisible Kid (a.k.a. Lyle Norg) shirks his duty during a Legion training exercise by visiting a dimension he can enter while invisible. He has fallen hopelessly in love with Myla, a resident of the other dimension, and plans to marry her.

But Myla has something to tell Lyle which proves so shocking it causes him to collapse and block her words from his memory.

Meanwhile, the Legion learns of an impending threat. One of their deadliest enemies, the mindless monster Validus, is barreling toward earth to attack them. The Legion can’t figure out how, since Validus can only be controlled by his master, Tharok—a half-man/half-robot—who is currently undergoing emergency surgery on his robot half in prison.

Validus lays waste to several Legionnaires, including Superboy, before Invisible Kid realizes what's going on: the monster is being controlled by a component of Tharok’s robot brain which the Legion kept as a souvenir. (Yes, super-heroes used to do that sort of thing. Batman had a huge trophy room in the Batcave, and Superman kept souvenirs in his Fortress of Solitude.)

|

Invisible Kid -- licked, but seeing

it through. |

But just as Invisible Kid is about to destroy the robot brain, Validus bursts into the Legion Museum and grabs the hero. As Lyle crushes the brain with his bare hand, Validus, in turn, crushes the life out of him.

Grieving, the Legionnaires receive an unexpected visitor: Myla. The girl from the other dimension reveals she could not marry Lyle before because she's a ghost. But now that Lyle is dead, they can be together in her dimension forever.

So the story ends on a paradoxically positive note. The Legion loses a member, but they are assured he will, at last, be happy.

What Works: A Hero We Care For

Upon rereading this story, I was struck by how little fanfare was made of Invisible Kid’s passing. Nothing on the cover or splash page indicates a character is going to die. (Comics publishers are notorious for announcing deaths well in advance and dropping cover hints as subtle as bricks, as in the case of Ferro Lad, a previous Legionnaire who died.)

As a result, Invisible Kid’s death is truly shocking and heart-wrenching.

Yet the story develops from a very traditional set-up and execution. Like most comics of that time, it is new-reader friendly. One can understand this story with very little prior knowledge of the Legion.

Bates also sets Invisible Kid up as a traditional protagonist—he’s the one we care for. Lyle is in love and something (we don’t know what) prevents him from being with his love. Nevertheless, he wins our hearts by being determined to bring Myla back to our dimension as his wife.

Displaying his skill at weaving subplots, Bates develops not one but two mysteries. First there's the mystery of what Myla said that shocked Invisible Kid. (No jokes, please, about phantom pregnancies!) Then there’s the mystery of who or what is controlling Validus.

The second mystery is particularly well played: The robot brain is visible in several panels, first disassembled and then in stages of self-repair—images that mean nothing to the reader until Lyle puts it all together for us (which makes it fun to flip back to previous pages and see that he was right).

Then there’s the death scene itself. Alone and facing a gigantic enemy, Lyle stands his ground and does what he must, even though it costs him his life—the very definition of a hero.

(Side note: I’m currently reading Harper Lee’s classic, To Kill a Mockingbird, in which Atticus Finch tells his daughter, eight-year-old Scout, the definition of courage: “It’s when you know you’re licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what. You rarely win, but sometimes you do.” In his own way, Bates made an equally profound statement by showing Invisible Kid's courage in action.)

What Doesn’t Work?

Very little, actually. “Massacre by Remote Control” is a product of DC Comics of its time, which means it offers little character development. Most Legionnaires serve the needs of the plot and do not come off as distinct personalities. (This is true even of Invisible Kid, who, to a degree, comes off as deep as a typical TV guest-star of the time.)

|

Is Superboy crying, too, or is he

just constipated? |

The most obvious example is Phantom Girl, who, filling a typical role for a female character of that time, has little to do except give Lyle someone to talk to and cry for him at the end (because, you know, it would be umanly for Superboy and Mon-El to cry). She doesn’t even get to use her powers, although she could easily evade Mon-El during the training exercise.

Some fans criticize the “happily ever after” ending as a sentiment that went out of style with the ‘60s. But I disagree.

If anything, the ending offers a bold, hopeful statement about the possibility of an afterlife. Bates never says Lyle went to heaven, but he leaves room for readers to interpret the ending through our own beliefs.

A Death to Remember

Killing off a beloved character always causes controversy, but these days such storms are often short-lived and hyped by a media that doesn’t know or care that comic book deaths are temporary.

(And even Lyle’s death proved somewhat temporary. A brief and ill-thought-out attempt to bring the character back floundered in the early ‘80s, and, of course, different versions of Invisible Kid have lived on in successive Legion “reboots”.)

But the death of Invisible Kid proved controversial for altogether different and more sustaining reasons. He died at a time when comic book deaths were rare enough to be permanent and in a way that left fans with mixed feelings. Yes, it was sad to lose him, but it would have been even sadder to bring him back and wrench him away from eternal happiness.

If you like this post, you may also like: