I often do my best writing in restaurants and coffee shops,

so I had pen and notebook in hand. As such, I was poised to jot down the

conversation of the couple next me (who were talking so loud I couldn’t ignore

them).

Their conversation went something like this:

Woman: If someone was banging your head against concrete twenty times and you had a gun, what would you do?

Man: I’d shoot him.

Woman: That’s right. And that’s exactly what he did. What people don’t understand is that kids are doing what they’re not supposed to be doing and going where they don’t belong. [Later:] George Zimmerman has been consistent in every one of his statements.

They were talking, of course, about Zimmerman's trial in the February 2012 shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, FL. The trial has dominated the news, and, thanks to certain fast food chains’ ubiquitous television

screens, you can't avoid it even while eating a breakfast burrito.

Events in the news have a way of intruding into

our fictional worlds, as well. Listening to the couple's conversation

(no matter how much I tried not to) drove away any desire to write about kids

with super-powers. How could it not? A real kid is dead, and a man is on trial

for murder.

Reality Vs. Fiction?

It’s hard not to watch news coverage of this story or to listen to discussions about it and not form an opinion. Judging by Facebook posts, viewers are already becoming polarized into one camp or another, just as they were during the OJ Simpson trial nearly 20 years ago.

It’s hard not to watch news coverage of this story or to listen to discussions about it and not form an opinion. Judging by Facebook posts, viewers are already becoming polarized into one camp or another, just as they were during the OJ Simpson trial nearly 20 years ago.

In a way, polarization is understandable. Just as nature

abhors a vacuum, so, too, do our brains abhor lack of information. We hate

suspending judgment and letting others (say, a jury) decide. We want answers. We want them now.

Everyone seems convinced they know what went down that night

in Florida and who is responsible.

Really?

If the truth were that easy to uncover, Zimmerman would have

been convicted or exonerated by now.

So, what are we supposed to do in the face of unspeakable,

senseless tragedies (and Trayvon Martin’s death surely is one, regardless of

who bears the blame)?

Turn to fiction.

Fiction: More than Escape

It may sound flip or clichéd, but fiction serves a more vital purpose than escapism. Fiction can actually help us make sense of reality and show us more positive ways of responding to tragedy. And insights from fiction can come from the most unexpected sources.

It may sound flip or clichéd, but fiction serves a more vital purpose than escapism. Fiction can actually help us make sense of reality and show us more positive ways of responding to tragedy. And insights from fiction can come from the most unexpected sources.

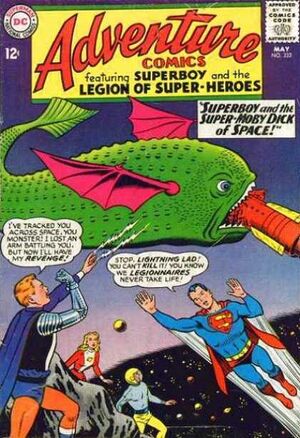

While reviewing classic stories for the Legion World message board this week, I re-read Adventure

Comics # 332, May 1965. Adventure # 332, written by Edmond Hamilton and drawn by

John Forte, is notable for two reasons. It

features a rather silly looking green monster called the Super-Moby Dick of

Space, and it’s one of the first comic book stories ever, if not the first, in

which a super-hero is crippled.

Summaries and reviews of the story can be found here,

but what struck me the most while re-reading it is how timely this story remains today.

|

| Copr. & TM DC Comics Inc. |

Wounded war veterans, the treatment they have received (or,

too often, the appalling lack thereof), and their difficulties in adjusting to

civilian life have been much in the news lately, and deservedly so. Our culture

continues its love affair with violence and war, judging by summer blockbusters, while the sacrifices of real heroes—soldiers,

firefighters, police officers, or teachers shielding children from harm—are

given cursory acknowledgement, if anything.

Mirroring what can happen to real-life heroes, Lightning Lad in this story loses an arm in the line of duty.

How Heroes Respond to Tragedy

At first, he responds the way you would expect. Bitterly, he vows to track down the creature responsible and kill it. His thirst for revenge is so great that his teammates question his mental stability. He recklessly endangers a spaceship while pursuing the creature.

At first, he responds the way you would expect. Bitterly, he vows to track down the creature responsible and kill it. His thirst for revenge is so great that his teammates question his mental stability. He recklessly endangers a spaceship while pursuing the creature.

The story borrows heavily from its literary source, Herman

Melville’s Moby-Dick, in this regard,

but, unlike Melville’s Captain Ahab, Lightning Lad comes to his senses and

finds a way to render the creature harmless without killing it.

In other words, Lightning Lad shows that it is indeed

possible to overcome passion and rise above the desire for

revenge (which too often is confused with justice).

Spectators who argue so passionately for one side or the

other in the Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman case were not personally injured

by the tragedy. Yet many react as though they were.

As I said, such reactions are understandable. A young man is dead. We want answers.

Yet reacting to events out of anger and rushing to judgment

is not healthy, either for individuals or for society.

How Should the Rest of Us (Who are Not Heroes But Maybe Want to Be) Respond?

So, what is a healthy response to senseless tragedy?

So, what is a healthy response to senseless tragedy?

Read a book.

Any book will usually do, but fiction works best.

Do not even look for answers. Answers—or, more accurately, insights—will come when least expected.

Most importantly, do not rely exclusively on the news for everything you need to know about the case. Our 24-hour news cycle has the paradoxical effect of giving us too much information and not enough context from which to draw meaningful conclusions.

More, the editorial slants of certain news programs feed into our prejudices and past experiences. In the absence of more objective information, we draw on emotional sources to complete the picture.

It is not wrong to have an opinion or to express it. But opinions can be mistaken for facts, and even facts can be distorted to support whatever opinion is already held. (Did Martin really bang Zimmerman's head against concrete twenty times, as the woman in the restaurant implied? And if so, did he do so because he was afraid for his life—as anyone facing someone with a gun would be—or was he just a mean kid who went somewhere he didn't "belong"? How does she know?)

If you don't know all the answers, it's okay to know that you don't.

Read a book.

No comments:

Post a Comment